Scaling a Minimalist Wall With Bright, Shiny Colors

Scaling a Minimalist Wall With Bright, Shiny Colors

by HOLLAND COTTER New York Times, Published: January 15, 2008

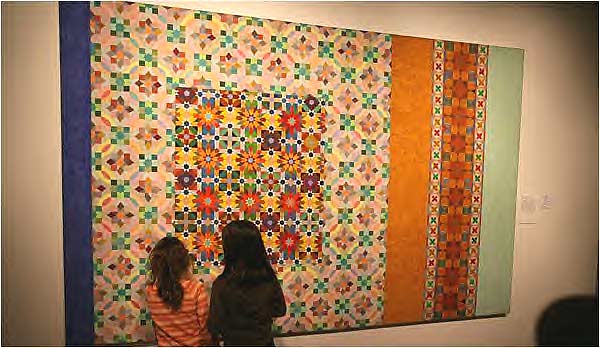

Joyce Kozloff's "Hidden Chambers" (1975-76) at the Hudson River Museum

YONKERS - "Pattern and Decoration: An Ideal Vision in American Art, 1975-1985," at the Hudson River Museum, documents the last genuine art movement of the 20th century, which was also the first and only art movement of the postmodern era and may well prove to be the last art movement ever.

We don't do art movements anymore. We do brand names (Neo-Geo); we do promotional drives ("Painting is back!"); we do industry trends (art fairs, M.F.A students at Chelsea galleries, etc.). But now the market is too large, its mechanism too corporate, its dependence on instant stars and products too strong to support the kind of collective thinking and sustained application of thought that have defined movements as such.

Pattern and Decoration, known as P&D, was the real thing. The artists were friends, friends of friends or students of friends. Most were painters, with distinctive styles but similar interests and experiences. All had had exposure to, if not immersion in, the liberation politics of the 1960s and early '70s, notably feminism. All were alienated by dominant movements like Minimalism.

They were also acutely aware of the universe of cultures that lay beyond or beneath Euro-American horizons, and of the alternative models they offered for art. Varieties of art from Asia, Africa and the Middle East, as well as folk traditions in the West, blurred distinctions between art and design, high and low, object and idea. They used abstract design as a primary form and ornament as an end in itself. They took beauty, whatever that meant, as a given.

P&D artists were scattered geographically. Some - Robert Kushner, Kim MacConnel, Miriam Schapiro - were in California. Others - Cynthia Carlson, Brad Davis, Valerie Jaudon, Jane Kaufman, Joyce Kozloff, Tony Robbin, Ned Smyth, Robert Zakanitch - were in New York. As a group they found an eloquent advocate in the critic and historian Amy Goldin, who was immersed in the study of Islamic art. And they had an early commercial outlet in the Holly Solomon Gallery in SoHo.

They all asked the same basic question: When faced with a big, blank, obstructing Minimalist wall, too tall, wide and firmly in place to get over or around, what do you do? And they answered: You paint it in bright patterns, or hang pretty pictures on it, or drape it with spangled light-catching fabrics. The wall may eventually collapse under the accumulated decorative weight. But at least it will look great.

And where do you find your patterns and pictures and fabrics? In places where Modernism had rarely looked before: in quilts and wallpapers and printed fabrics; in Art Deco glassware and Victorian valentines. You might take the search far afield, as most of these artists did.

They looked at Roman and Byzantine mosaics in Italy, Islamic tiles in Spain and North Africa. They went to Turkey for flower-covered embroideries, to Iran and India for carpets and miniatures, and to Manhattan's Lower East Side for knockoffs of these. Then they took everything back to their studios and made a new art from it.

Ms. Kaufman turned 19th-century American quilt designs into abstract nocturnes glinting with sewn-on beads. Mr. Zakanitch went for flowers in monumental paintings based on fabrics remembered from his childhood home in New Jersey. Ms. Schapiro also drew on floral images in a type of feminist-inspired collage she called "femmage." And in her "Gates of Paradise" (1980) she applied domestic crafts materials - lace, ribbons, fabric trim and so on - to a theme associated with Lorenzo Ghiberti.

Ms. Carlson's all-over tweedlike patterns, done with repeated strokes of thick paint, are less specific in their references. And even if Ms. Jaudon doesn't insist on Islamic art as a source for her crisp interlace designs, it surely had some effect. Ms. Kozloff is forthright about the debt she owes to Moroccan and Mexican tile work. Her melding of brilliant colors with a basic Minimalist grid has yielded generous results in public architectural projects, and in her poetic and intensely political recent art.

Mr. Davis and Mr. Smyth lie a little outside the general P&D loop, one doing figurative work and the other mosaics. Mr. Robbin, who lived in Iran as a child, conflates geometric Persian motifs with others from Japanese silk kimonos. For Mr. MacConnel and Mr. Kushner, textiles themselves are a primary medium.

Mr. MacConnel glues pieces of Near Eastern and Southeast Asian fabric together into suspended open-work hangings. Mr. Kushner, who studied with Mr. MacConnel and traveled with Ms. Goldin to the Middle East, originally draped his painted fabric pieces over his own body in performances. One festive piece in the show, "Visions Beyond the Pearly Curtain," is shaped like a chador, cape or kimono, although with its gathered swags and melon-orange curlicues it has the theatrical punch of a rococo opera curtain about to rise.

When Mr. Kushner finished this piece in 1975, P&D was taking off. It had avid collectors in the United States; in Europe it was a hit. Then interest dried up. Worse than that, in America the movement became an object of disdain and dismissal.

There were reasons. Art associated with feminism has always had a hostile press. And there was the beauty thing. In the neo-Expressionist, neo-Conceptualist late 1980s, no one knew what to make of hearts, Turkish flowers, wallpaper and arabesques.

Thanks to multiculturalism and identity politics, we know better what to make of them now; the art world's horizons are immeasurably wider than they were two decades ago (without being all that wide). Besides, to my eye, most P&D art isn't beautiful and never was, not in any classical way. It's funky, funny, fussy, perverse, obsessive, riotous, accumulative, awkward, hypnotic, all evident even in the fairly tame selections by Anne Swartz, the curator for this show.

And not-quite-beauty is exactly what saved it, what gave it weight, weight enough to bring down the great Western Minimalist wall for a while and bring the rest of the world in. Let the art historical record show, in the postmovement future, the continuing debt we owe it for that.